Note: Coverage has returned to Latin Europe after a brief focus on Italy, and the site name (formerly Ambulatin) has been updated to reflect the original scope.

French geographer Jean-François Gravier described the extreme primacy of Paris as a case of urban macrocephaly, or an overconcentration around a single dominant pole. In his influential 1947 book Paris et le désert français (Paris and the French desert), he traces this imbalance to a chain of historical choices: monarchs like Louis XIV drawing elites to Versailles; the French Revolution’s deep distrust of the provinces as potential counter-revolutionary strongholds; and Napoleon, followed by later regimes, sticking with centralization because it was seen as efficient, controllable, and stabilizing.

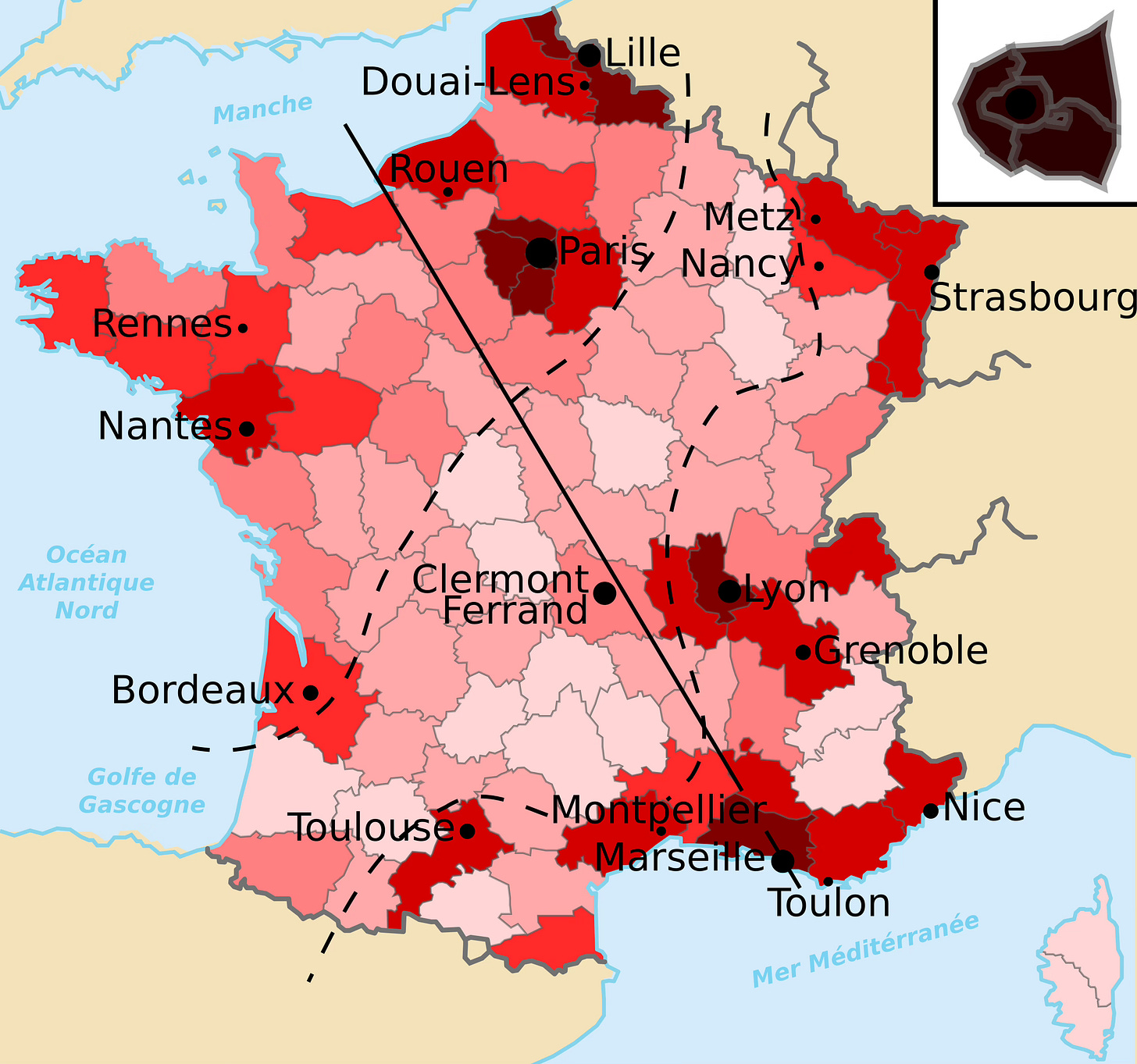

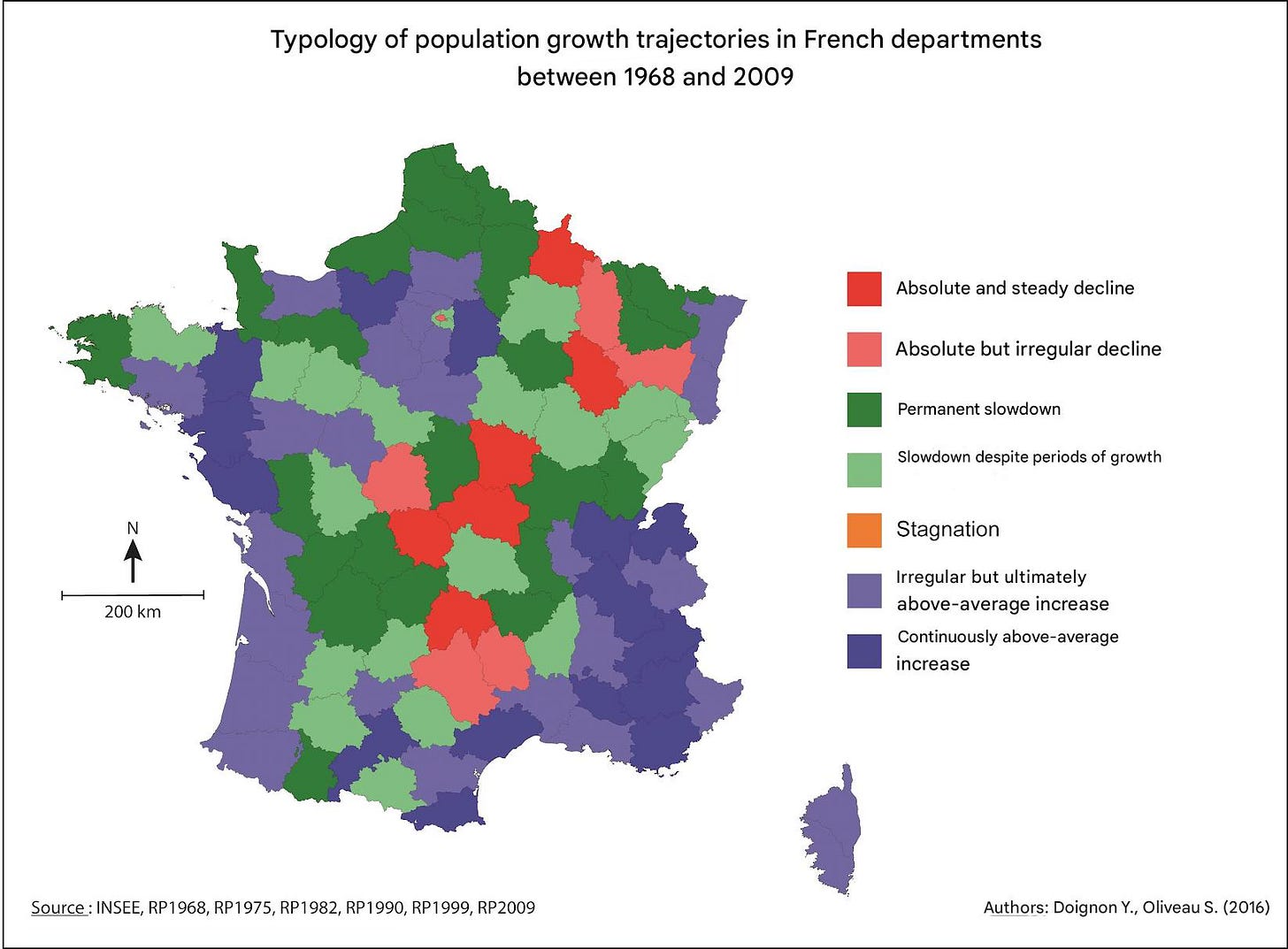

These large swaths of the mainland suffering from low population density and divestment, known as the diagonale du vide (empty diagonal), extend from the Ardennes to the Pyrenees via the Massif Central. These trends were already apparent to 19th-century observers.

At its 1884 congress, the Société des Géographes Français - concerned about the exode rural - warned about the depopulation and demographic stagnation of vast areas of the country. A few decades later, in the same intellectual milieu, the father of French geography Paul Vidal de la Blache explored his interest in the relationship between man and his environment in his 1904 book Tableau de la géographie de la France1. He paid particular attention to how industrialization and rapid urban growth were reshaping settlement patterns.

The main concern is not just where people settle but how demographic changes affect the sociability threshold. Once an area drops below it, schools close, shops disappear, services vanish, and social networks thin out. This was particularly relevant during the so-called Trente Glorieuses2 which saw industrial expansion, rising living standards, urbanization, and the growth of the welfare state.

One issue with diagnosing the empty diagonal in any era is the shifting definitions of French administrative divisions: departments, cantons and municipalities [1]. This difficulty stems from the instability of territorial units throughout history. After the 1790 creation of the départements, the two most significant shifts of this type were the late-19th-century adjustments of communes and cantons alongside the rise of modern statistics, and the post-1960s reorganization that created régions and intercommunal bodies, changing how population and activity are counted.

Territory in language

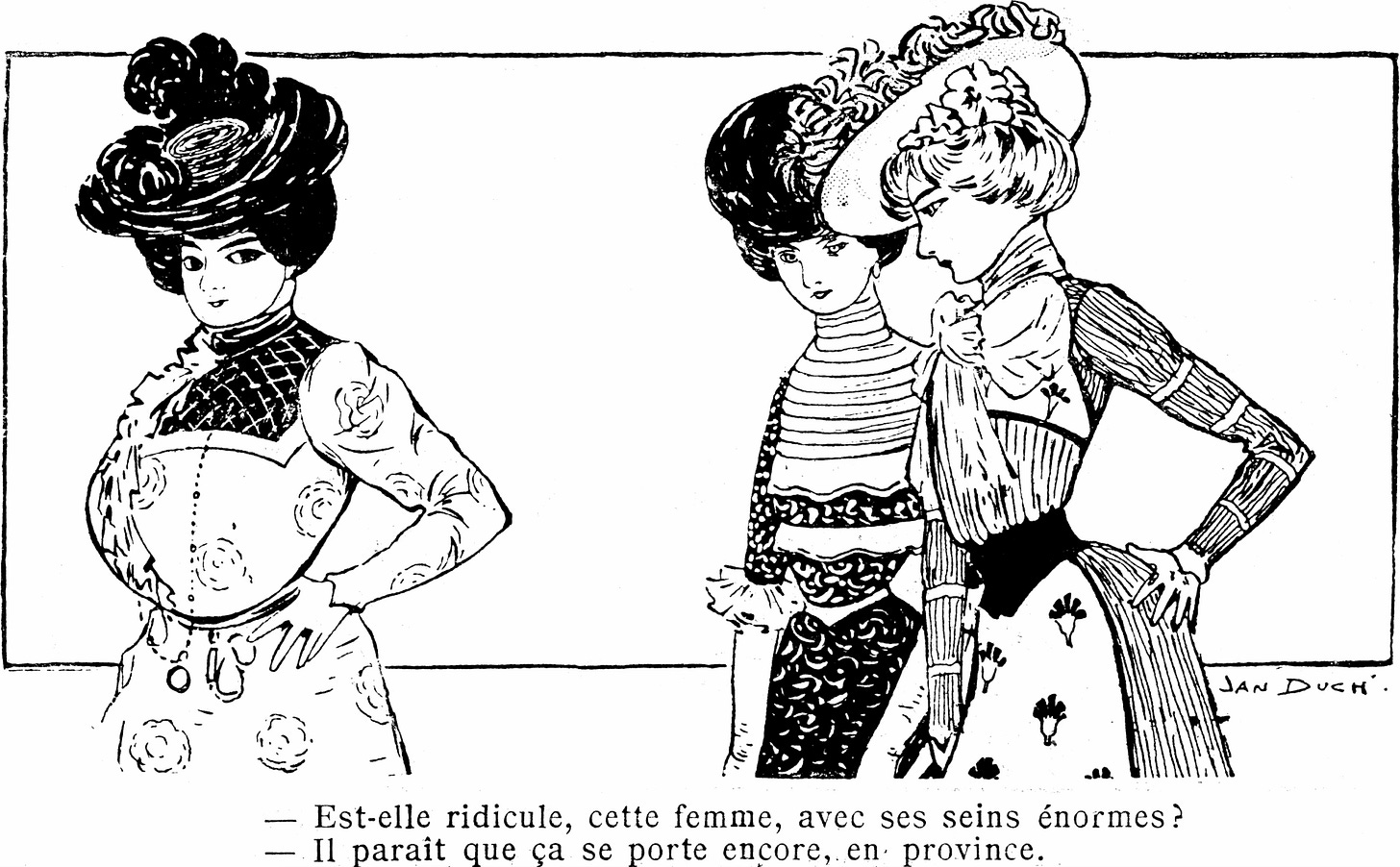

Linguistics also play a role in determining how society views macrocephalic changes. The term parisianisme - initially meaning a linguistic or cultural trait of a Parisian - underwent semantic drift towards the pejorative. A modern interpretation is more aligned with a contemptuous attitude that distinguishes what happens in Paris as being more important than what happens elsewhere in the country. It contrasts with the terms province and provincial in French. From pro + vincere (“to conquer”), it speaks to subordination; a territory brought under control.

Nineteenth-century literature crystallized this opposition. Balzac famously framed France as split between Paris and a jealous, diminishing province, a view repeated throughout the century. Dictionaries later fixed this meaning in language itself, defining provincial as gauche or lacking distinction. And writers from Goncourt to Mauriac reinforced the image of provincial life as stagnant and dull.

Language doesn’t only demean the province; it can also empty it of identity. Marc Augé’s notion of the non-lieu (or non-place), captures this shift, where certain spaces are no longer even described as inferior, but as functionally anonymous and culturally unworthy of mention.

Industry & inequality

It is not just historical configurations and negative connotations that define these geographical differences. Industry and services can change the fate of entire areas of the country. For example, agriculture’s economic role varies sharply across territories. High-yield cereal regions in the Paris Basin or highly specialized wine areas like Champagne are well integrated into global markets, while medium-mountain regions where one finds extensive mixed farming remain far less profitable and weakly connected to wider economic networks.

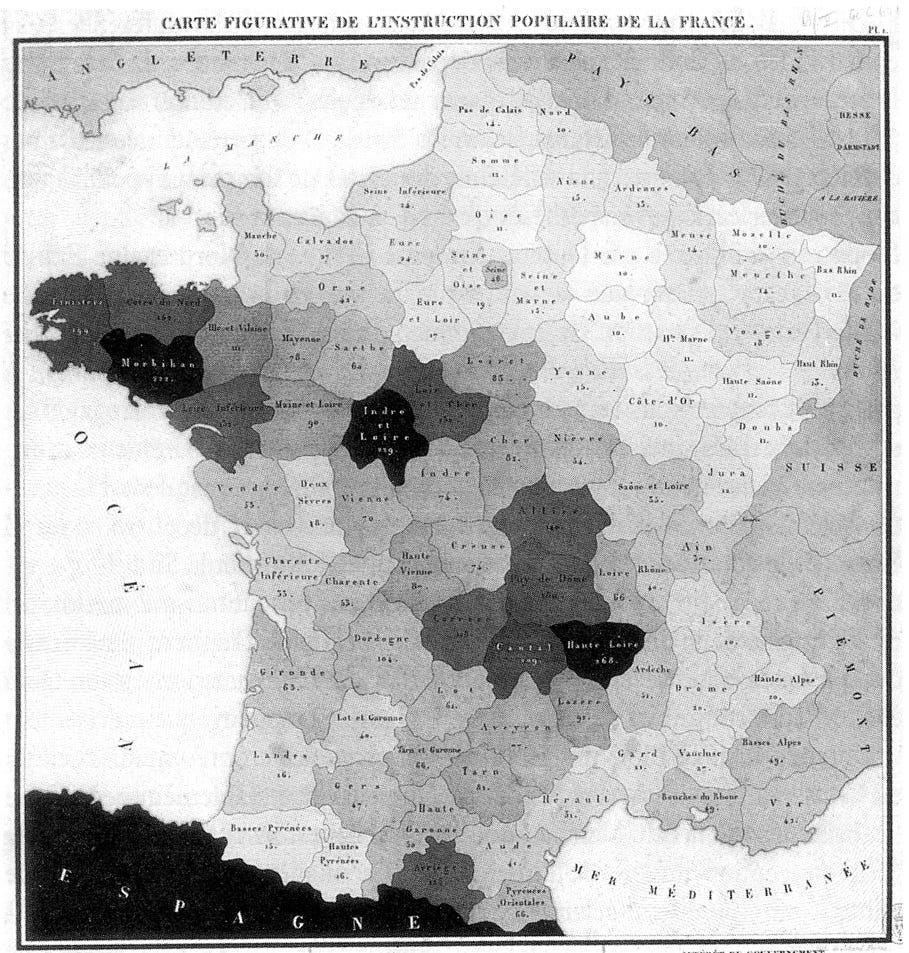

In 1827, mathematician Charles Dupin highlighted the Saint-Malo-Geneva line, a statistical northwest–southeast figurative boundary illustrating early industrial vs. agrarian regions. Later commentators have linked it conceptually to the idea of the empty diagonal. In his treatise, he divides France into North and South, according to productive and commercial forces, stating [2]:

The division is by no means arbitrary; the two parts it presents contain two populations that differ more from each other, in wealth, industry, and education, than France as a whole differs from the three British kingdoms, similarly taken as a whole.

Dupin’s figurative Map of the Popular Instruction of France above is the world’s first choropleth map3, depicting the availability of basic education in France by department. In it, he highlights the aforementioned the Saint-Malo-Geneva line, showing the “enlightened France” of the North and the “dark France” of the South.

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, industrialization and infrastructure - from railways to roads - gradually reinforced these regional contrasts. Northern and eastern France became more urbanized and industrially dynamic, while many southern and mountainous areas remained mostly rural, with their economies tied to small-scale farming and local markets.

From the 1950s onward, the French state tried to counterbalance Parisian overconcentration through decentralizing industry. By limiting new industrial construction in Île-de-France and pushing these companies toward provincial cities - often with subsidies - it aimed to take pressure off Paris and to spur regional growth. This approach was later organized through DATAR4, which promoted “equilibrium metropolises” to encourage development outside Paris.

This logic fits within aménagement du territoire, a distinctly French way of treating space as a political and economic problem. After WWII, territory was thought of as something to be actively organized, including populations, industries, and infrastructures. Over time, especially from the 1980s onward, this model weakened with decentralization and European integration, giving way to more competition and fragmentation.

Along with these policies, French geographers popularized a new divide called the Le Havre–Marseille line, separating more dynamic eastern areas from agricultural western ones, to the east of which about 60 % of the French population lives.

Conclusion

Paris et le désert français highlighted the country’s overreliance on Paris, creating a lasting and memorable metaphor. Gravier not only described the gaps but framed them as a structural pathology. That framing directly led to postwar aménagement du territoire thinking.

He deliberately used harsh, provocative language against cities, perhaps to shock readers and draw attention to his argument. His ruralist and authoritarian assumptions show how deeply anti-urban and anti-Paris ideas shaped early policy around territories. While many of his claims didn’t age well, the core idea of a Paris-province divide remained. Later planners and policy adopted his views of the imbalance more so than his proposed solutions. Even as the opposition shifted, from Paris vs province to cities vs peripheries, the metaphor continued to influence thinking and keep his work relevant.

France’s unusually early decline in fertility around the turn of the 19th century made these contrasts visible sooner. Of course, low birth rates didn’t create the inequality but they made it difficult to self-correct. In areas outside the cities, departures weren’t being offset by births, while Paris and a few large cities continued to increase their populations through migration. This unevenness helped keep regional differences in place. Ultimately, the story of Paris and the provinces reveals how historical patterns of settlement and policy created lasting regional contrasts.

Additional information

1 - Les voyages de Mat: Diagonale du vide

A diagonal journey through rural France, in words and images. 2500 km off the beaten track to discover the least populated departments of France and meet those for whom life is here.

Sources

1 - La diagonale se vide? Analyse spatiale exploratoire des décroissances démographiques en France métropolitaine depuis 50 ans

2 - Forces productives et commerciales de la France (pg 249)

Vidal de la Blache was also the central figure of the “possibilist” school, which states that the environment sets limits, but humans choose how to act within them.

the roughly thirty years of strong economic growth in France from 1945 to 1975

such a map provides an easy way to visualize how a variable varies across a geographic area or show the level of variability within a region

a government agency created in 1963 to coordinate regional planning and development policies

Brillaint breakdown of how centralization compounds itself. That sociability threshold concept really clarifies why rural areas cant just bounce back once they pass a certain point. I've seen similiar patterns play out in midwest towns back home where school closures practically sealed the fate of entire communities. What's intresting is whether remote work might actually start reversing some of this, or if people still cluster digitally around the same metro hubs anyway.