While Italy’s North-South divide often focuses on the South’s economic struggles, the medieval city-republics of the North (ex. Venice, Genoa, Milan, and Florence) built a unique tradition of cooperation among citizens, merchant guilds, and generalized trust among strangers. This puts them closer to the high-trust cultures of northern Europe than to the more family-focused, top-down patterns in the South.

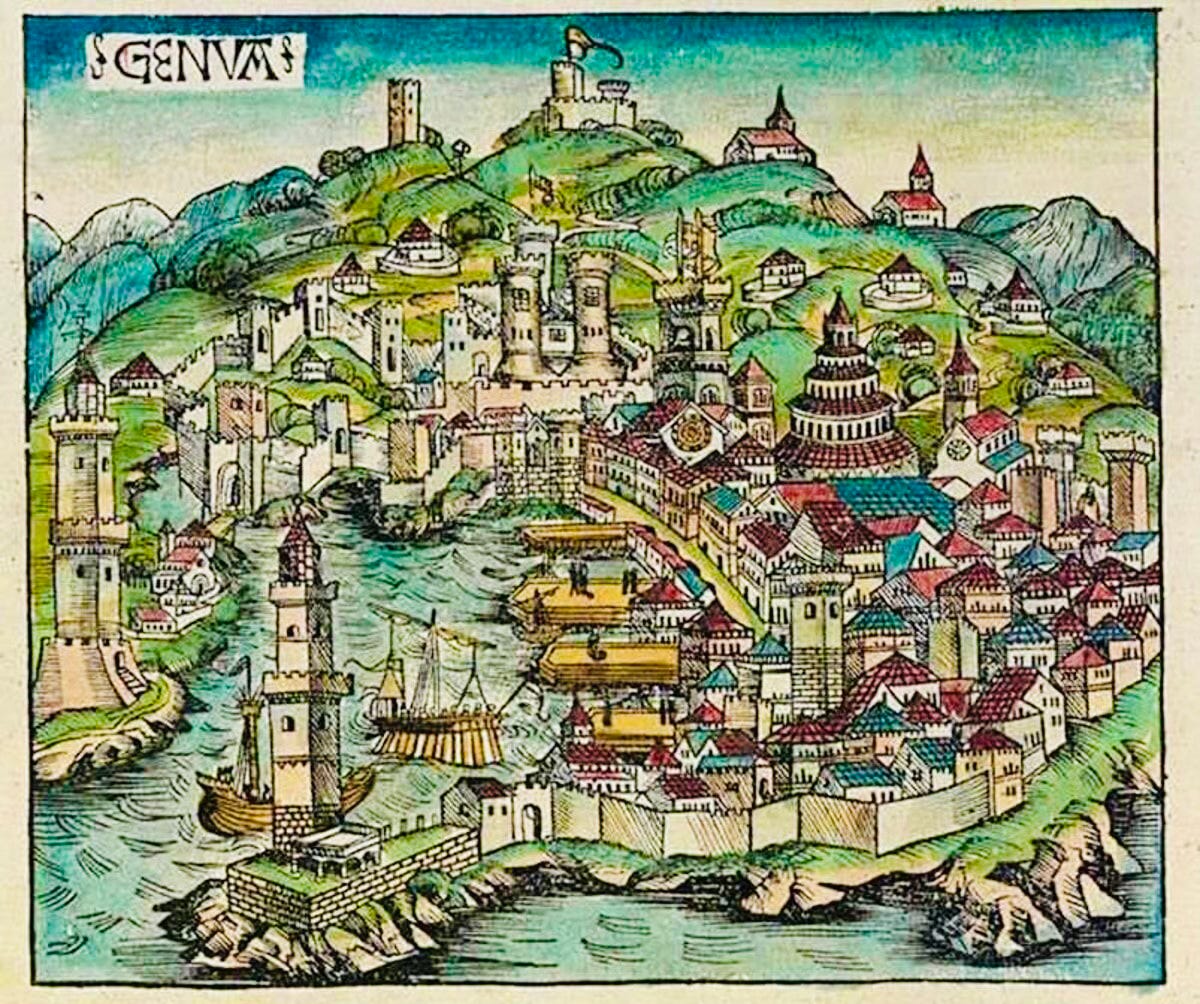

In an era before centralized authority existed, protection was provided by the city itself. These so-called communes, in the late 11th and early 12th centuries, were at the center of self-governing corporations where residents swore oaths of mutual defense and peace-keeping. Born from a compromise between feudal nobility and a rising bourgeoisie1, these northern Italian communes grew in ways that other autonomy movements in Europe2 couldn’t. In places like France and England, strengthening national monarchies kept similar experiments in check.

This type of self-organization was a result of a secularization process that ocurred between the High and Late Middle Ages with the growth of the bourgeois-mercantile class. This arose from advancements in agriculture that led to a population boom, which freed up labor and intensified competition. Under these conditions, practicing a trade became more rational, with time seen less as a divine gift and more as a practical resource to be measured and managed.

The Commercial Revolution and Renaissance humanism pushed this shift further by bringing practical calculation into everyday economic life. Tools like double-entry bookkeeping and Arabic numerals helped organize trade, while logic and arithmetic were taught to prepare people for business. Legal tools such as insurance separated risk from individual fate, making commerce more rule-based and less dependent on personal or family ties.

Hanseatic & Protestant influences

Northern Italian cities were part of a bigger European picture, not examples in isolation. Like the Hanseatic League up north, cities such as Lübeck and Hamburg started out in the late 12th century as small groups of towns and merchants banding together to protect trade and expand their markets. Over the next couple of centuries, that loose network grew to include hundreds of towns across northern and central Europe, with shared rules, protections, and tightly connected commercial and family networks.

Northern Italy did something very similar. In Venice, the Arsenale and merchant tribunals managed trade and settled disputes, while Genoa used consulates and merchant guilds to protect contracts and organize long-distance commerce. Meanwhile, Milan’s artisan guilds set standards, ran apprenticeships, and managed local markets. Many cities, including Florence, had a podestà (a magistrate who enforced the law and kept the peace) and later a capitano del popolo (a representative for artisans and small merchants who balanced the podestà’s authority).

These institutions shaped who held power. In Florence, the popolo grasso (wealthy merchants and bankers belonging to major guilds) dominated political life, while the popolo minuto (lower classes of artisans and laborers) had far less influence. Across northern Italy, this combination of guilds, magistrates, and civic representatives created a structured, high-trust environment that let commerce and cooperation grow beyond the family or neighborhood, essentially copying the networks of the Hanseatic League.

Before the rise of communes and these mercantile networks, trust in Europe was mostly limited to family, clan, or village. Broader society lacked the institutions and norms needed for cooperation among strangers, making high-trust interactions rare and even risky. Northern Italian cities helped build that framework, spreading trust horizontally through guilds, contracts, and public duties.

Later developments, such as the Protestant Reformation in northern Europe, reinforced these patterns. Promoting literacy, civic responsibility, and social accountability, the Reformation encouraged individuals to engage directly with texts, think independently, and adopt the kind of ethics that lead to dependability, honesty, and honoring contracts. These cultural changes increased the society-wide trust and forward-looking behavior that northern Italian communes had already started establishing, further setting high-trust regions apart from those dominated by hierarchical or kin-based structures3.

Contributing factors

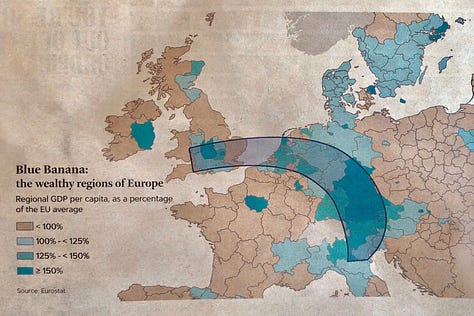

The economic and civic energy of northern Italy fits into bigger patterns across Europe. The French geographer Roger Brunet noticed a difference between “active” and “passive” spaces and, in 1989, described a West European “backbone” (aka Blue Banana), an urban-industrial corridor running from northern England through the Rhine Valley to northern Italy, especially Turin, Milan, and Genoa. For Brunet, this European Backbone wasn’t something new. It grew out of long-standing historical factors, from medieval trade routes to the buildup of industrial capital, showing how geography and existing infrastructure helped some regions develop faster than others.

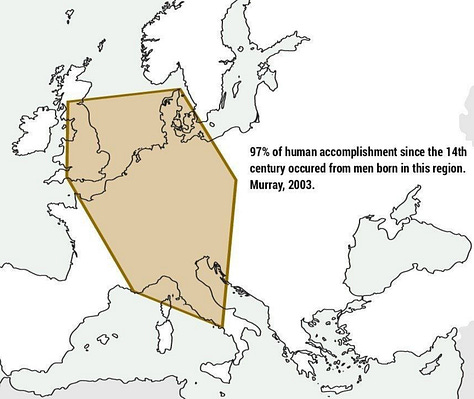

Northern Italy’s role shows up in patterns of human achievement too. Charles Murray, in Human Accomplishment, measured contributions to the arts and sciences between 1400 and 1950 and found that most came from Western, Central, and Southern Europe. This suggests that northern Italy’s medieval communes’ combined commercial density with unusually high literacy and durable civic institutions created conditions that supported cultural production over long periods rather than in short bursts.

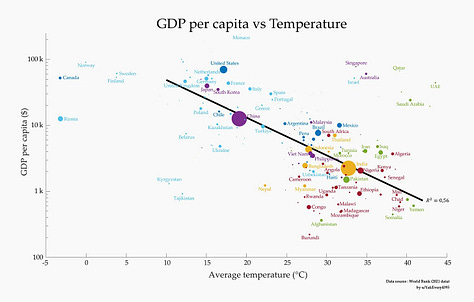

Climate may be a third factor. In colder, seasonal environments, survival depended on anticipating future conditions, such as storing food, building shelter, and organizing labor in order to survive. In warmer, stable climates, there was less pressure to think ahead or innovate. Over generations, this kind of seasonal pressure could favor societies that are more organized and forward-looking. Seasonal thinking may have reinforced the advantages of the European core, helping explain why northern Italy, along with other backbone regions, became a hub of innovation and development.

Taken together, these factors help define what I’m calling the questione settentrionale, or Northern Question. Northern Italy followed a different regional trajectory, rooted in structures that proved remarkably durable.

bourgeoisie, from the Medieval Latin burgus, meaning fortified settlement or quarter that was extramuro (outside the walls of a castle). These were where artisans, merchants, doctors, and notaries resided

such as Ghent, Bruges, Nuremberg and Swiss cantons

applicable to most of Southern Europe