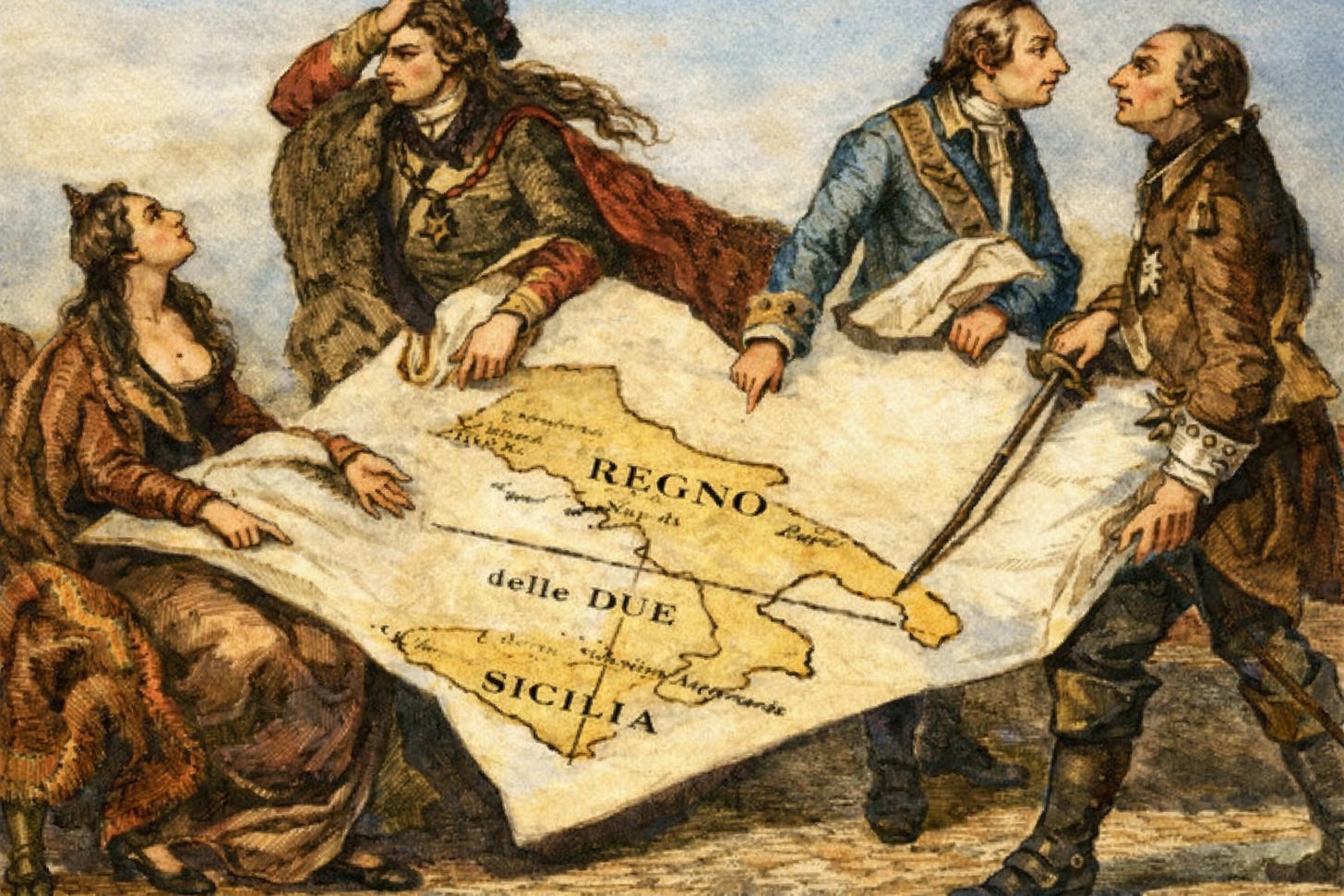

Four decades after unification, southern Italy exposed the limits of a unified state. Political unity had been achieved, but the administrative kind required managed integration once it became clear the South wouldn’t catch up on its own. The Kingdom of Naples, for example, had long operated with weaker institutions, different land systems, and centralized rule. Unification in 1861, however, didn’t fix this. It simply transplanted Piedmontese law (setting the standards by which the rest of Italy would be judged) onto a very different society.

A unified Italy, while beneficial in the long term, stripped power, status, and control not only from the Kingdom of Naples but from the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The result was fiscal pressure, social unrest marked by revolts and repression, widespread rural banditry, mass emigration to the Americas, recurring cholera outbreaks, and fragile local institutions.

Naples had already been singled out for state intervention with the 1885 Legge Napoli, aimed at urban and sanitary renewal. It was the first recognition that the city required separate treatment1. And while it did achieve limited success in its aims, it also displaced poor residents and failed to revive the city’s economy.

Amid a banking crisis and general unrest in the 1890s, momentum built for a renewed attempt at fixing lingering issues, but on a broader scale. The official response came in the form of the Legge Speciale per Napoli of 1904 which removed or reduced customs taxes on raw materials and consumer goods, among other measures that sought to boost employment and industry. Again, the results were mixed but it was the first real attempt to address the “Questione meridionale” (Southern Question) through economic and industrial policy on a regional level rather than merely city-wide, like the 1885 law.

Southern Question

The expression “Southern Question” refers to the age-old internal political dilemma between the North and the South of the nation, determined by economic, civil, social, and cultural imbalance. There are many causes for the divide.

The origins are often traced back to the medieval period. Much of the North experienced a long communal phase, in which self-governing cities developed civic institutions, commercial law, and local administrative traditions. Meanwhile, the South remained under centralized monarchies and never developed the same culture of municipal autonomy.

This divide was reinforced by centuries of foreign rule. Under Spain, the South was governed as part of a wider imperial system. Northern Italy, on the other hand, was more closely tied to more advanced French and central European administrative and economic models.

Geography and culture deepened the differences. The Po Valley’s flat and fertile terrain and trade routes favored commerce and early industrialization, while northern dialects formed more continuous linguistic zones. Southern dialects, influenced by political centralization and regional separation, as well as Greek and Arabic, evolved more independently, strengthening long-standing regional differences.

After effects

The after effects of the two Neapolitan laws were many - including on urban planning. The 1885 post-cholera law was behind the landfill that buried the historic Chiaia beach (once a sweeping sandy shore celebrated in Grand Tour-era paintings) beneath the Caracciolo promenade found today. Two decades later, the 1904 law placed massive steelworks in the Bagnoli quarter, transforming the pristine Phlegraean bay, once envisioned by famed architect Lamont Young as a Neapolitan Venice, into an industrial zone [1].

As the 1904 law attracted northern investors to establish heavy industries, they ended up absorbing local firms and providing short-term employment gains in an era of continued corruption. It also paid for better electricity, trade schools, worker housing, and a bigger port to increase trade, but most of the grand plans to reshape the city never got off the ground [2].

Nonetheless, it can’t be argued that there was a mini-boom, that is, a rapid industrial surge in Naples between 1904 and 1914. If it weren’t for WWI, perhaps Naples might have potentially rivaled northern cities, but the war redirected state contracts to northern firms2, forcing southern factory closures and cheap acquisitions. This ties into a broader argument on how the conflict strengthened the North-South divide by prioritizing the industrial triangle of Milan, Turin and Genoa [3].

Critics, however, ultimately viewed the law as being too narrowly focused, neglecting broader southern regions and creating economic dependency on northern capital - a trend that continued in the interwar and post-war periods. More than a century later, the debate persists. Administrative law professor Giovanni Leone has argued that any further special laws solely for Naples would reinforce harmful stereotypes of the city [4]:

Naples has always been considered an exception. “Napoli è Napoli.” “Bella e maledetta.” “Unica e impossibile.” “Napoli non è l’Italia: è un mondo a sé.” Expressions repeated for centuries, clichés so deeply rooted that they have become tradition. But this tendency to exaggerate Naples’ uniqueness risks, according to some, pushing the community into a corner. “Naples does not need parochialism or populism,” Leone stresses. “The city is part of a country that is central to Europe, and it is from this perspective that we must think.”

Leone argues that special laws and initiatives for Naples are consistently partial and reactive. Instead, he advocates a national agency dedicated to the entire Mezzogiorno3, capable of channeling resources (including a reversed north-south allocation of EU funds), prioritizing sustainable infrastructure, and shielding projects from organized crime4.

More than a century after the 1904 law’s partial efforts to incentivize Naples’ industrial revival, the Southern Question persists not only economically but, as economist Pasquale Saraceno observed in 1989, as an “ethical-political” challenge to Italy’s national unity [5]. Only a unified vision, that sees the Mezzogiorno’s potential as integral to Italy’s future, can finally move the country beyond the divisions it inherited from unification.

Additional information

1 - How Italy Became the Most Divided Country in Europe [29m]

2 - La Napoli Del Futuro - Il Sogno di Lamont Young [50m, subtitles]

3 - Sud: questione meridionale o nazionale? [54m]

Sources

1 - 1884-1904, i vent’anni del delitto di Stato: quando Napoli fu privata del suo mare

2 - Legge speciale per Napoli e mini boom economico di inizio Novecento

3 - Quando il Nord comprò La Campania

4 - “Per rilanciare Napoli e il Mezzogiorno serve un’agenzia nazionale”, la proposta di Giovanni Leone

5 - Questione meridionale ancora aperta. Superare il divario tra Nord e Sud centrale per ritrovare unità nazionale

though some say it “hid” speculation behind hygiene needs, benefiting Piedmontese banks

it could easily be argued that this happened simply due to existing capacity and logistics

the other term for Southern Italy

a prime example is what happens in Siciliy, the Incompiuto Siciliano